Writing, for me, is less about “creativity,” even though that’s the way writing is taught in typical university courses.

Then again, academicians might not be the best judges or teachers of writing. How many academics today, after all, could pen something like Hamlet? What professor of prose could author anything as memorable as the Gettysburg Address?

Writing, for me, is more about discovery. Writing is discovering.

Every written piece, if it is serious, contains within it what my teacher’s teacher, Leo Strauss, called “logographic necessity.”

Logos is the Greek word for logic or reason. Logos also means word, or articulate speech, or argumentation, without which reason can neither exist nor function (which, by the way, makes for an interesting interpretation of the first line of the Book of John: “In the beginning was the Word [logos], and the Word [logos] was with God, and the Word [logos] was God.”)

The job of the writer is to discover, or to to see with the mind’s eye the logos contained within the message, the story, the argument, and then craft language in a way that helps the ideas to emerge, to be revealed, and to be seen and understood by readers, rather than remaining concealed.

The ideas buried inside every written piece and waiting to be discerned, qua ideas, are in themselves perfect and unchanging.

But words and all other parts of language are human constructions. We human beings invent the symbols and sounds of language and assign meaning to them.

As a human construction, language often falls short of the ideas we want to describe, prescribe, or rescribe. Language often fails us, clouding rather than illuminating ideas.

That is why writing, or at least writing well, is an art. Writing is the art of arranging language so that both author and reader might see clearly the logos, the logic, the idea. The art of writing, therefore, often becomes an act of discovery for writers who catch a glimpse of an idea with their own mind and aim to share it with the minds of others.

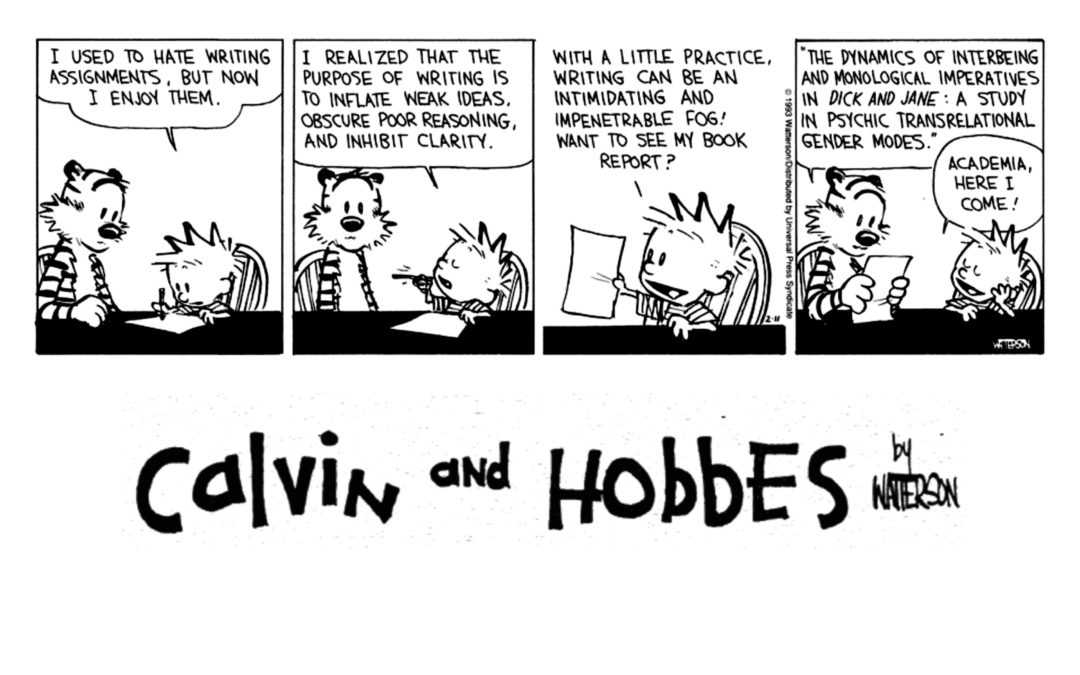

I love Calvin and Hobbes as an example of artful writing and effective persuasion. I have pasted above of my favorites that makes my point, at several levels. Interestingly, Bill Watterson, the author of Calvin and Hobbes, when he was in college, was a student of a student of Leo Strauss. As was I.

And on that note, the end of this piece now points back to the beginning, which is always a good time to stop writing.