Lincoln’s speech was part of a ceremony dedicating a cemetery created to bury the many dead following the horrific Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863). In only three days of fighting, the Union and Confederate forces combined suffered a staggering 50,000 casualties.

Below are some reflections on Lincoln’s Address at Gettysburg, in no particular order.

ANCIENT AND SACRED

There is a tradition of dedicating cemeteries, the most sacred and holy of any ground in most cities, dating back to antiquity.

The cause of the solemnity surrounding these dead-filled grounds was that most people, throughout most of history, believed the gods who protected them, guided them, and occasionally blessed them with gifts, were the ghosts of the city fathers, the first family members who gave the first laws to a tribe or clan. (See, for example, The Ancient City, written by Fustel de Coulanges and originally published in 1864.)

How remains of the dead were treated, in the eyes of most ancient people, was therefore a life and death matter. Literally. Burial grounds were sacred because they were the points that connected the living and the dead, a bridge of sorts between worlds, to be feared and treaded with the greatest respect and reverence.

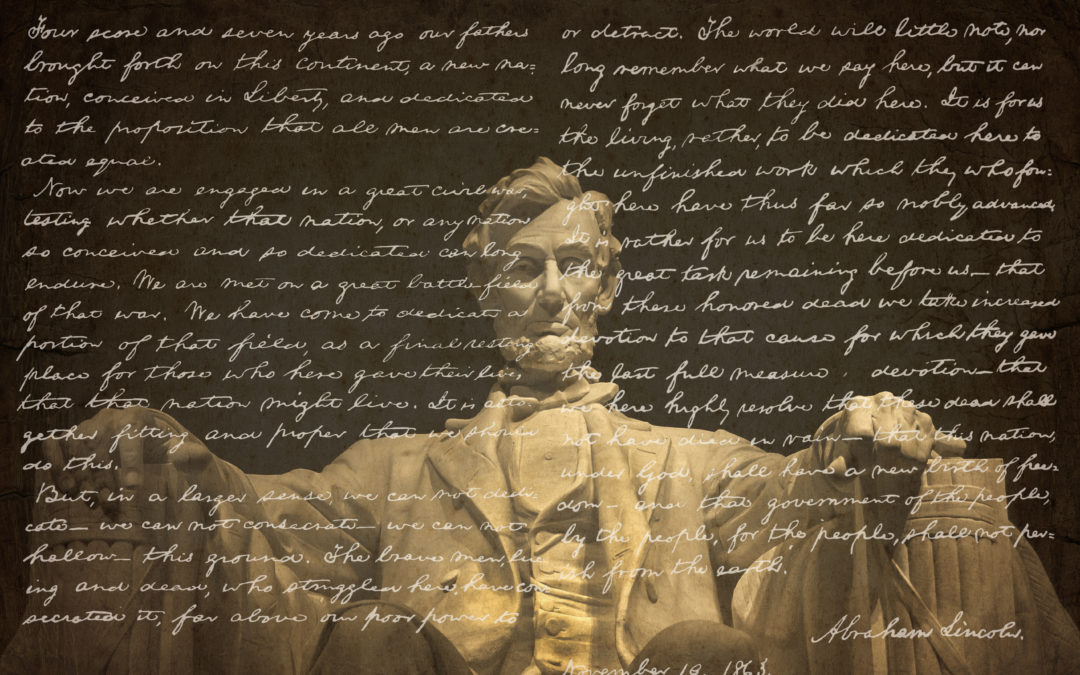

GETTYSBURG: SPEECH HEARD ’ROUND THE WORLD

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is known across the globe. People living in distant, remote lands might know little of the United States. But they likely know of Lincoln. And they likely know of the Gettysburg Address.

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address rightly deserves comparison to the famed funeral oration offered by Pericles, the ancient Athenian statesman, in the course of the Peloponnesian War. Some scholars have drawn this comparison and certainly there are similarities.

In my opinion, however, the speech delivered by the American Abraham exceeds in almost every way the oration of the Great Greek Pericles. Lincoln accomplished in 272 words what no one—Pericles included—had ever done before or has ever done since.

The Gettysburg Address is a work of rhetorical perfection. I do not think it can be improved or edited in any way.

CONCEPTION AND BIRTH

The literary framework for the speech is the most special, miraculous, tender, beautiful and sacred of human things: Conception and Birth.

The speech opens by describing America as being “conceived” in liberty. The speech closes with a call to a “new birth of freedom.”

Conception and birth—the emergence of life!—forms the opening and closing theme of the Gettysburg Address.

CONTRASTS

The speech contains pulls and pushes in opposing emotional directions by offering great contrasts:

- The Living vs. The Dead

- Then vs. Now

- Speech vs. Action

- What Others Did vs. What We Must Now Do

- Last Full Measure of Devotion vs. Resolve To Go On

NO NAME-CALLING

There are no proper nouns in the Gettysburg Address. No one is identified by name.

Further, even though there was a great war raging as Lincoln spoke, he placed no blame on anyone. He never referenced the South, or the single greatest cause of the war: slavery.

This was a war between citizens, between brothers, after all. So, instead of blaming, Lincoln described the war as a test of whether a nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal “can long endure.”

Whether we would pass or fail that test would be determined, ultimately, by all Americans, North and South, white and black, men and women.

UNDERSTATEMENT

The Gettysburg Address contains perhaps the greatest use of understatement ever: Lincoln said that “the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.”

Today, does anyone other than a few history buffs remember who was at the Battle of Gettysburg or what they did? No. But EVERYONE notes and remembers what Lincoln said there.

At Gettysburg, word eclipsed action.

DEDICATION MORE FOR LIVING THAN DEAD

The key movement of the speech turns the focus from the dead to the living. Though the ceremony is to “dedicate” a battlefield cemetery, Lincoln turns the meaning of “dedication” to focus on the living:

“It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.”

The living, in a decisive respect, are more important than the dead—even though we honor what the dead did and all that the dead sacrificed.

But the work of those now dead is done. The hardest work is ahead, for the living. It is the living who are in need of fortification and inspiration and focused dedication. The dead might deserve praise, but they are in little need of it.

LET’S DATE

The memorable dating of the Gettysburg Address, in the opening line, is key to understanding it the entire speech.

When Lincoln in 1863 referred to “four scour and seven years ago”—87 years ago—he was referencing 1776. And what important thing happened in 1776? The Declaration of Independence was approved July 4, 1776. That is our Independence Day. The Declaration of Independence, in other words, was the foundation upon which Lincoln built in his Gettysburg Address.

The ideas enshrined in the Declaration of Independence—

- that all human beings are equally human,

- that the natural equality among human beings contains important moral and political principles,

- that every human being possesses an equal natural right to his own mind, body, and property,

- that the only purpose of government is to protect those rights we possess by nature, not as gifts from government that can be given or taken by fiat

—formed the core of all of Lincoln’s moral and political views. These same ideas were the core of the original Republican Party platform, upon which Lincoln was elected President in 1860.

What might the United States look like if Republicans today remembered the noble, principled beginnings of their own party? One can only speculate.

APPLES OF GOLD IN PICTURES OF SILVER

For Lincoln, the principles of the Declaration—not the text itself, but the ideas represented by the text—are the foundation for all political right, all political justice.

As he once remarked, natural human equality is the “father of all moral principles in us.” On another occasion, he described the relationship between the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution thus:

All this is not the result of accident. It has a philosophical cause. Without the Constitution and the Union, we could not have attained the result; but even these, are not the primary cause of our great prosperity. There is something back of these, entwining itself more closely about the human heart. That something, is the principle of Liberty to All—the principle that clears the path for all—gives hope to all—and, by consequence, enterprise and industry to all.

The expression of that principle, in our Declaration of Independence, was most happy and fortunate. Without this, as well as with it, we could have declared our independence of Great Britain; but without it, we could not, I think, have secured our free government and consequent prosperity. No oppressed people will fight and endure, as our fathers did, without the promise of something better than a mere change of masters.

The assertion of that principle, at that time, was the word fitly spoken which has proved an apple of gold to us. The Union, and the Constitution, are the picture of silver, subsequently framed around it. The picture was made not to conceal or destroy the apple; but to adorn and preserve it. The picture was made for the apple—not the apple for the picture. So let us act, that neither picture, nor apple shall ever be blurred, or bruised or broken. That we may so act we must study and understand the points of danger.

-Lincoln, 1861

OPENING OUR MINDS

Read the Gettysburg Address. Then re-read it. Reflect. Study. Let it transport your own thinking to that which is ancient as well as that which is timeless, high, and the source of everything we consider to be good.

It took Lincoln thirty years to be able to write that magisterial speech. Spend some time unravelling its many rhetorical, philosophic, and poetic nuances. The effort will pay you back. Much. And be happy that you, my friends, were fortunate enough to be born in this United States of America—far from perfect, yet still “the last best hope of Earth,” in the words of Abraham Lincoln.