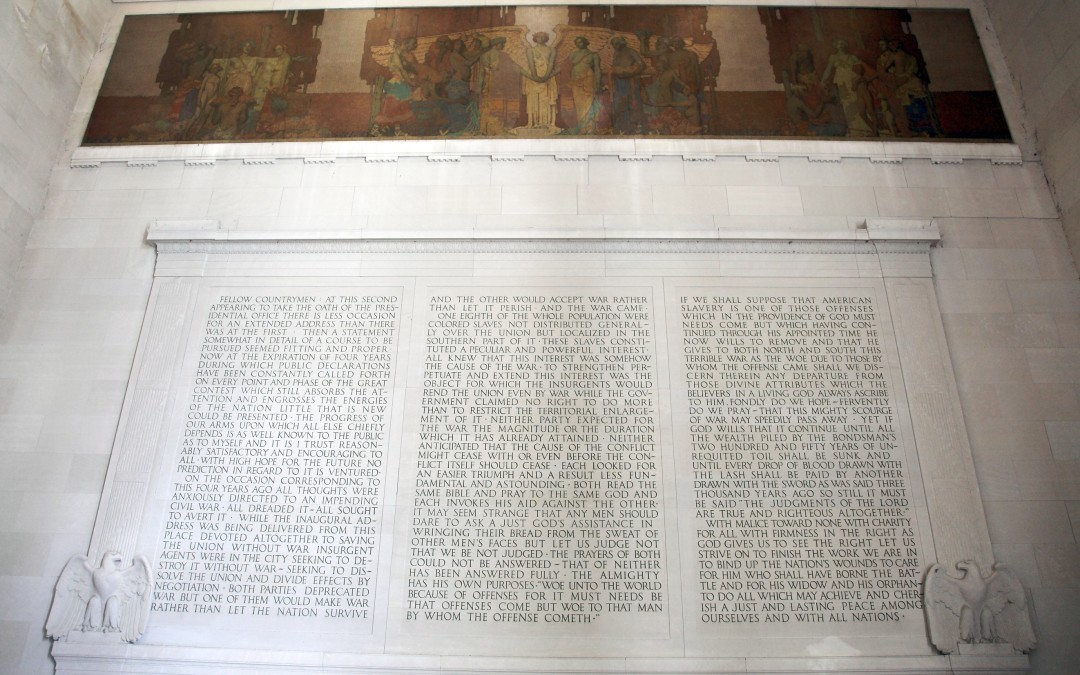

This week marks the 150th anniversary of one of the most striking, peculiar, and somber of all presidential speeches: Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, delivered March 4, 1865, etched forever on the wall of the Lincoln Memorial.

Much can be said about that speech, and much that has been said perhaps shouldn’t. Misguidance, mistakes, and confusion are always-present dangers when lesser minds attempt to interpret or explain greater minds. That is among the reasons I have always eschewed textbooks in my teaching: Why rely on some second, third, or fourth-rate commentary of an original text, when one can simply read the original text and try to understand for oneself the mind who wrote it?

THE FIRST INAUGURAL ADDRESS

Here I will offer merely a snapshot of the depths of Lincoln’s mind by way of a comparison between his First and Second Inaugural. The First Inaugural, March 4, 1861, came in the midst of immense uncertainty: Seven southern states had passed ordinances of secession just prior to Lincoln taking office as President. And, at least in the minds of some within those states, they had already claimed to have left the Union of the United States and thereby the authority of the U.S. Constitution.

The remaining four states that would complete the Confederate States of America had yet to secede. How many states would go? How many would stay? How serious were those southerners who had signed papers declaring secession? Would the South fight to defend its newly proclaimed sovereignty? Would the North fight to maintain a Union? No one knew the answers to these questions, including Lincoln. Yet, when he stood to be sworn into office, no shots had been fired. There was no war. Emotions were high, it’s true, but there was still relative peace across the land, North and South.

Accordingly, Lincoln’s First Inaugural was hopeful, optimistic. Like philosophy, I believe Lincoln hoped for a movement from the way things had been to an understanding of truth and an implementation of it in public policy, especially the truth regarding the gross immorality and injustice of slavery. Thus I find it to be no coincidence that Lincoln opened his First Inaugural with an appeal to tradition – “In compliance with a custom…” – but concluded on the much firmer ground of nature, which is the main subject of all philosophic inquiry: “the better angels of our nature.”

The movement from tradition to nature is the movement of philosophy. It is the movement of all true “enlightenment” of the human mind. It is the beginning of all genuine understanding and serious thinking. Parochialism concerns itself with tradition, rooted in history. Philosophy concerns itself with truth, rooted in nature. In this way, philosophy is eternally optimistic. In this way, philosophy is “comedic,” in the ancient sense of the term. In this way, Lincoln’s First Inaugural is comedy. It is optimistic.

THE SECOND INAUGURAL ADDRESS

But the scene of the Second Inaugural was very different. In four short years, body counts had grown to hundreds of thousands. Death, destruction, devastation, and depression had darkened the land. The nauseating stench of rotting flesh filled one’s nostrils; the sight of burned buildings and homes saddened one’s eyes. The purpose and the meaning of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural, therefore, was very different than the First.

In his Second Inaugural, Lincoln opened: “At this second appearing…” The invocation of a “second appearance” or a “second coming” clearly was an appeal to the deep Christian beliefs of the American people of his day. Lincoln knew his audience well. And he closed with an equally Biblical theme: “peace…among nations.”

The movement from the First to the Second Inaugural represents a movement from philosophy to theology. If philosophy is characterized by optimism – the endless hope that one can learn more, understand more – then theology is represented by a kind of resignation – knowing what man is by knowing what he is not and how he eternally must fall short.

SOCRATES LAUGHS, JESUS WEEPS

Theology begins with the resigned premise that man is not God, never will be God, and that man begins and always will remain “fallen” in comparison with God. Theology begins with the premise that there exists a living, conscious, willful being of infinitely greater importance than living, conscious, willful human beings. And thus the movement from philosophy to theology is a movement from comedy to tragedy – Socrates is thrice reported to have laughed, never to have wept, while Jesus is thrice reported to have wept, never to have laughed.

And that, perhaps, is why the movement from Lincoln’s First to his Second Inaugural is a movement from philosophy to theology, from optimism to resignation, from comedy to tragedy – a movement that would’ve resonated with any American who had witnessed the horrors of the American Civil War.