“Law is reason absent passion.”

—Aristotle, The Politics

“Reason … is the voice of God.”

—Rev. Samuel West, sermon: “On the Right to Rebel Against Governors,” 1776

The American Founding was a unique blending of political elements, part ancient, part modern. The Americans understood their own revolution in mostly modern terms. Unlike Aristotle, who taught “revolution” as the unending transformation of regimes from one form to another, the Americans described revolution as an overturning of the existing unjust political order.

PART MODERN

In the Declaration of Independence, for example, the American people announce that their intention is “to dissolve the political bands” that have connected them to another people, namely the English. The Americans hoped to build upon the firm ground of eternal natural right a kind novus ordo seclorum, a new order of the ages, something unknown to classical thinkers.

There are many other modern elements in the American Founding, among them:

- The concept of universal natural rights, inherent in human nature and shared equally by all mankind, an idea unknown to the ancient world.

- The rejection of divine right monarchy, Papism, religious persecution, and theocracy in all forms, and the corresponding disestablishment of the church. In America, one’s rights would not depend upon a confession of sectarian faith, as Jefferson stated in the Virginia Statute of Religious Liberty.

- The principle that any government lacking the consent of the governed is morally illegitimate.

- A written and widely respected constitution that clearly defines and limits the power of the government authorized by the people, with a view that the only purpose of government is to secure natural rights, not save souls.

- The protection of a large realm of individual privacy, where citizens are free to pursue happiness, worship God as they choose, employ their labor as they see best, keep what they produce and earn, and speak their minds openly, all without government interference.

Still, it is nonetheless true that there were important classical features about the American Founding as well.

PART CLASSICAL

Among the paradoxes of the early American experiment in self-government is the fact that immediately following a modern revolution, America experienced a founding that was very classical in character, complete with law-giving “founders” and “founding fathers”—something common among the ancients, but highly unusual in the modern world.

The choice of pseudonym used by the authors of The Federalist Papers, “Publius,” was borrowed from the Roman statesman Publius Valerius Publicola (“Publicola” meant “friend of the people”), harkening the authority of classical Roman republicanism.

While many Anti-Federalist critics of the proposed 1787 Constitution chose as pen names those who attended the demise of the Roman Republic, such as Brutus and Cato, Hamilton outmaneuvered them by writing under the name of one who helped to found the Roman Republic by overthrowing the Roman monarchy.

More: Unlike the scenes of bloody chaos unleashed by the French Revolution, in which revolution devoured itself and was brought to a stop only by the heavy hand of Napoleon, the Americans quickly moved from overturning unjust laws to giving new, better laws. The Federalist Papers were written not merely to defend the newly drafted Constitution, but to help educate Americans and begin forming a constitutional soul of the American people, not unlike the role of “preludes” in Plato’s classical book, The Laws.

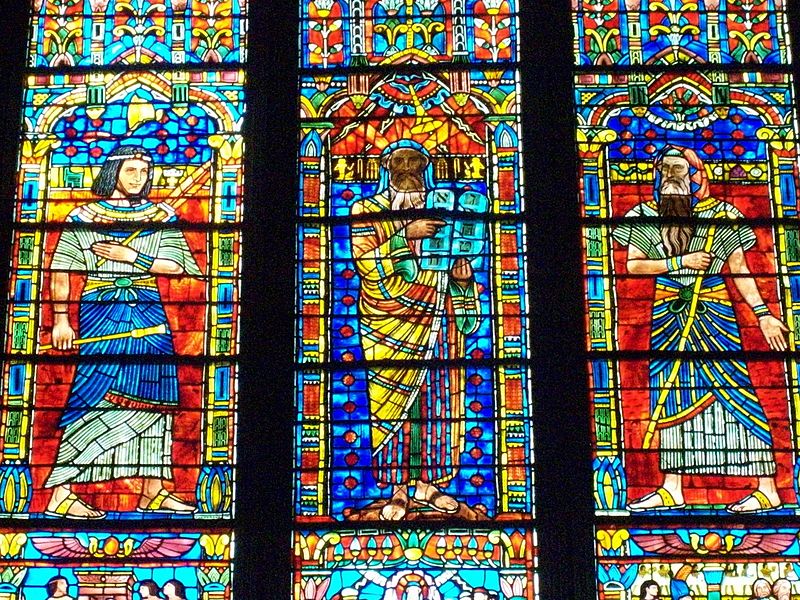

The teaching of Federalist 49, in particular, with its classical, Socratic definition of self-government as the rule of reason over passion, echoes yet another import classical theme in the American Founding, rooted in the deepest ground of classical Western political thought.

Thus we find the American Founding to be partly ancient, partly modern. Lesson over.